In October 2019, I was at Snape Maltings, near Aldeburgh and very much associated with Benjamin Britten, to record my first recital CD. Shortly to be released on Rubicon Classics, I was joined by my regular recital partner, German pianist David Meier – who I’ve known and worked with for ten years – and the Norwegian composer Peder Barratt-Due (as well as the recording team, of course). We spent three days recording six works in the Britten Studio in the very beautiful surroundings of the Maltings.

In October 2019, I was at Snape Maltings, near Aldeburgh and very much associated with Benjamin Britten, to record my first recital CD. Shortly to be released on Rubicon Classics, I was joined by my regular recital partner, German pianist David Meier – who I’ve known and worked with for ten years – and the Norwegian composer Peder Barratt-Due (as well as the recording team, of course). We spent three days recording six works in the Britten Studio in the very beautiful surroundings of the Maltings.

This is the first time I recorded a full recital CD with piano, so without any experience like this, I was really wondering how it would work out. The first day we started of recording Hindemith’s Sonata. The recording team were easy to work with and David was having a good time playing the entire repertoire from memory! At the end of the day I noticed the sound of my viola’s C-string wasn’t as good as it should be. It was kind of ‘tired’ and had a “buzzing” sound and I feared that it would be the same on the recording. It was! Therefore, with the producer, we decided to re-record some of the parts of the Hindemith Sonata again the next day, but with a new C-string.

Day two was probably the most intense day in the studio. We finished the Hindemith and Ysaÿe’s Caprice d’apres l’Etude en forme de Valse de Saint-Saëns before lunch break (after every morning session we had lunch in a café that offered really good dishes, which was very important to our energy in the recording sessions). In the afternoon we continued with Arthur Benjamin’s Sonata, a work I was really looking forward to record since the music is so exciting and fun. We ended the day with Enescu´s Conzertstück. I was so delighted to be able to finish up the day with a good rest, after all we been through.

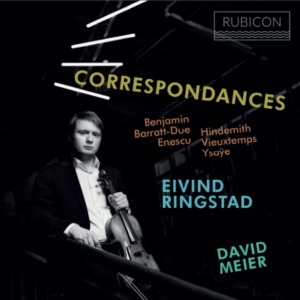

Recording Correspondances – Eivind Ringstad and David Meier. Photo Graham Johnson

Day three – the final day – we had become quite comfortable in the studio. We knew that we had a lot of time to finish the last two pieces. The Vieuxtemps Elégie was on our morning schedule. In the afternoon Peder Barratt-Due arrived and we were ready to embark on his piece. It was really enjoyable and exciting working together with Peder and the producer together. Both David and I were using our last energy on this session. Exhausted but delighted, we had finally finished our first recording together!

The name of new piece by Barratt-Due has given the title to the CD: Correspondances

Correspondances is named after one of Baudelaire’s poems and I like the fact that, amongst its meanings, the English translation – ‘correspondences’ – refers to responding mutually to one another. In a deep sense I believe that is what chamber music is all about, as we must continually react to each other in a fraction of a second. The viola and piano are contrasting instruments; a bow touching a string is very different from a string being struck by a felt-covered hammer and, as a result, the musicians relate differently to the initiation of a tone. To create a unified interpretation, the two players must move beyond these differences and connect through listening, as if not knowing what the other musician’s intentions are. In their coming together, they have to ‘correspond’ with each other.

In building the repertoire for the CD alongside the new work, I wanted to include famous pieces from the viola repertoire by Enescu, Hindemith and especially Vieuxtemps as I am very privileged to play on the 1768 ‘ex-Vieuxtemps’ G.B. Guadagnini viola. There’s a new transcription, by my fellow Norwegian Nils Thore Røsth, of Ysaÿe´s Caprice d’apres l’Etude en forme de Valse de Saint-Saëns and a more rarely performed work: the Viola Sonata by Arthur Benjamin which, when I delved into it, made me so excited that after my first performance of it I knew immediately I wanted to record it.

All in all, this greatly varied program is partly intended as a tribute to the versatility of the viola, which is usually characterised as a lyrical instrument with a dark and deep sound. Yet, I believe a viola has much more to offer, not least how captivating it is in the high register, as it can be radiantly brilliant, but also soft and shimmering. The viola is also not particularly known for being a virtuoso instrument. This however I find not to be true so, for the repertoire on this disc, I have chosen many works that display virtuosity on the viola exquisitely.

Let’s start with Correspondances, where Peder Barratt-Due explores the virtuosic capacities of both instruments, setting them free in swift and furious passages with the musicians’ ability to ‘correspond’ pushed to its limits. Peder asked himself a question:

L-R David Meier, Peder Barratt-Due and Eivind Ringstad listening to a playback of Correspondances. Photo Graham Johnson

” ‘What happens when we completely surrender ourselves to the world around us? ‘

“In the poem Correspondances by Baudelaire, from Les Fleurs du mal, the senses and the mind become one, one tastes what one sees, touches what one smells and sees what one hears; the world outside of one’s skull reflects back at the mind inside of it.

“I think that now, more than ever before, it is important to address how our surroundings affect us, how what our minds conjure is a result of the environment. Despite how trapped this might make us feel, it can be a source of something beautiful as long as we let it inspire, rather than discourage us.”

“At the invitation of the Royal Philharmonic Society and BBC New Generation Artist, Eivind Ringstad commissioned the Correspondances and he premièred it, with David Meier, at the 2018 Edinburgh International Festival. ”

Following the Edinburgh première, Peder has revised the work twice, resulting in the piece we recorded. You can read Baudelaire’s original poem and various translations here.

Recording Correspondances – Eivind Ringstad and David Meier. Photo Graham Johnson

Arthur Benjamin – perhaps best known for his Jamaican Rumba – wrote his Viola Sonata for William Primrose, having met the Scottish-Canadian violist during his many years in the United States. After the opening sorrowful Elegy, there is a melancholic Waltz introduced by the piano, before a contrasting middle section leads back to the Waltz and seamlessly interweaving material from the Elegy. The last movement, a lively and virtuosic Toccata, seems as influenced by South American music, as his Jamaican Rumba was by the Caribbean.

I like to imagine that Belgian virtuoso Henri Vieuxtemps composed his Op 30 Elégie actually on the viola I now play. He was regarded as one of the greatest violinists of his time alongside Ernst and Paganini. Amongst his prolific output, which includes six violin concertos, he also composed a small number of pieces for the viola, which he played himself. The Elégie, composed by Vieuxtemps while working in St Petersburg, is a melancholic piece inspired by the Italian operatic bel canto tradition. In sonata form, it opens softly in F minor with the piano playing a suppressed march, which underpins the viola’s main theme. A short viola cadenza leads to the contrasting middle section in A-flat major, expressing relief and nostalgia. Another cadenza leads back to the elegiac opening theme, this time developing into a coda with bravura passages in the viola.

Another famous Belgian violinist was Eugène Ysaÿe. Indeed, his teacher was Vieuxtemps and the influence between the two is very clear in the music. Ysaÿe is perhaps best known for his six solo violin Sonatas. But amongst his other works is a violin transcription of the last of French composer Camille Saint-Saëns’ six Études Op 52 for solo piano, which he turned into a capricious concert piece for violin and piano. The work is filled with lyrical melodies in waltz style combined with dazzling virtuosity and moments that are powerful and demonic, making it definitely an excellent choice for a viola transcription, made by my fellow Norwegian Nils Thore Røsth.

Britten Studio, Snape Maltings. Photo Graham Johnson

Romanian George Enescu spent much time of his life in Paris. His Conzertstück for viola and piano was composed as a competition piece, the result of a commission from Gabriel Fauré. While ensuring that the competition candidates had to tackle various technical challenges, with singing phrases for each individual string, graceful double-stops and dazzling passages, Enescu fashioned a musically dramatic concert piece in a rhapsodic form, combining French impressionism and Romanian folk elements.

Finally how could I not include a piece by Paul Hindemith? He was not only a great composer but one of the most important violists in history. He composed a vast amount of works for the instrument and his Sonata Op 11 No 4 stands out as especially popular with viola players and audience alike. In the opening dreamlike Fantasie, Hindemith’s harmonies and melodic lines are reminiscent of the impressionistic style, extending to the whole sonata. A folk theme introduces the second movement combining romantic and neoclassical elements which undergoes four variations before, attacca, we’re into the final movement. Contrasting pompous and lyrical moments, the finale includes three more variations on the folk theme, the last making for an exhilarating coda.